|

Historic Culture Preservation

Resources |

Charles Lummis’ Recordings |

Casa de Adobe Fiestas |

Other Contributers |

Contact |

Portal

Francisco Amate

A number of pieces from Francisco Amate’s repertoire

are preserved on Lummis’ wax cylinders.

This drawing is by Hernando Villa, a californio descendent whose own family was also featured in Charles Lummis’

recording

project. Although Hernando was himself a musician and singer, there are no Lummis recordings of him.

|

Once upon a time, in a land not so far away and a time not so long ago, a scattered

population of racially mixed pioneer settlers, soldiers and ex-convicts — guided

occasionally by the religious council of the Franciscan padres — sought paradise. Their children declared

themselves to be “hijos del país,” thus celebrating a positive self-identity in the face

of all outsider opinions to the contrary. They then proceeded to comport themselves in a manner that

they perceived as representing persons of class, thereby converting themselves into the otherwise

absent aristocracy.

The land was called Alta California, the time was the heyday of the California missions and ranchos

from the 1770s through the 1860s (more or less), and the people called themselves californios.

Travelers to the area were consistently impressed by the secular music and the social dances,

commenting often on the propensity of the californios to dance and sing — and particularly at times when the

largely Protestant observers thought they ought not to. And those same observers were also somewhat perturbed to observe that

the dance tunes from

Saturday night were being re-used in Sunday morning mass.

My object is to explore briefly a few aspects of the preservation of this California musical heritage —

a

largely oral tradition played by non-professional musicians with little or no formal music training.

Although related to both, this California music is not by and large Mexican and it is not Spanish.

It instead reflects the isolation from both the Spanish and Mexican mainstream of the settlers that played

it, and their self-identity as a separate society. Some pieces did come to California with settlers

coming from Mexico, bringing with them their already diverse heritage from Spanish, indigenous Mexican

and African roots. And there might be the occasional pureblooded first generation Spaniard who knew pieces

from the latest Italian operas or from popular zarzuelas. Some pieces came from other southwestern Hispanic

and Native American settlements, such as those in New Mexico, through circuitous trade routes and marriage.

Other pieces were written here, some came from the traditions of the local Native American musicians,

and some came with trade from passing ships.

With the coming of the American period and the sudden immigration of great quantities

of people from other places — particularly in northern California — the culture and heritage of the californio

began fading

away into the new dominant culture and merging into the growing Mexican immigrant community. In spite

of their protestations that they were “hijos del país” — somebodies, the cultural

manifestations of the californio culture were devalued and largely ignored except within the larger Mexican

and Latino communities.

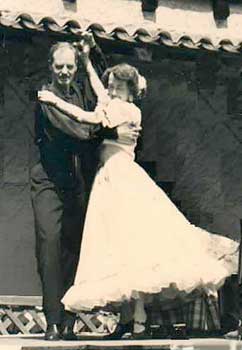

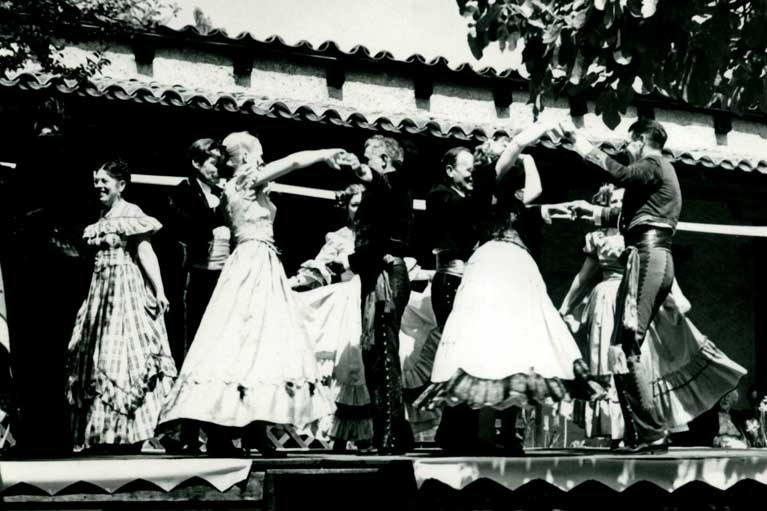

Historic photograph of an event at Olvera Street in Los Angeles

Courtesy Arnold Guerra

Los californios® Collection

Although these events have been criticized as

having been mere romantic fantasy, the participants believe they were

expressing pride in their historic California heritage.

|

Then came the need for the new American Californians to create for themselves

a self-identity — the new equivalent to declaring themselves “hijos del

país” — to create a “here” in California. This in a society that considered racism

natural, and that was still remembering the Alamo. In such a climate it is not surprising that a movement

to value the California history and heritage of both californios and of indios took a romantic “fantasy

heritage” turn — describing things to

be valued as “Spanish” rather than Mexican or Indian, and creating images of an idyllic past

where everyone lived a life of ease, and Franciscan padres were saints. In fact, it is more surprising

that the Spanish-language and indio cultures became recognized and valued at all.

It’s easy to criticize this romantic recasting of California history.

But it is due to this romanticization of the past that we still have today enough of the remnants

of this music to be able to recreate and preserve it. And it is due to that romantic image that the

persons who carried those thin threads of memory with them into the twentieth century were able

to attain sufficient respect for those threads to be preserved. Continuing resurgences of these

romantic revivals from time to time were able to preserve direct links to this historic past through

the 1950s, such that those of us who came behind are still able to tap into those resources.

Resources for Preservation of this Historic Culture

Manuel Ferrer |

William J. McCoy |

Eleanor Hague |

Aurelio M. Espinosa |

Historic Disk Recordings

Manuel Ferrer

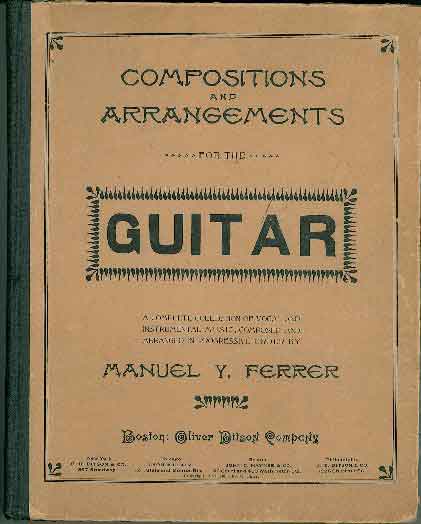

Compositions and Arrangements, by Manuel Y. Ferrer.

First published in 1882 by Mattius Gray. This edition is from 1910.

Los californios® Collection.

|

Manuel Ferrer, born in Baja California in 1828 and moving to Alta California

at a young age, studied guitar in the mid 1840s with Narciso Durán, one of the Franciscan

missionaries in California.

In turn, Ferrer became an influential performer, teacher and composer —

particularly in San Francisco — from about 1850. His instructional book of guitar pieces,

including a section of songs, was first published in 1882 by Mattius Gray.

This 227-page work is an eclectic mix of pieces, and includes such pieces as:

Lejos de ella:

Also sung for Lummis by

Mrs. Melba Melsing & Mercedes García

Spanish Melody No. 2:

The same as the tune for Ángel tutelar,

sung for Lummis by Adalaida Kamp

El jazmín

La cacha

El vestido azul

Spanish Mazurka (No. 1 & No. 2)

Spanish Melody No. 1

La súplica:

Composed by another californio guitarist & composer,

Miguel S. Arévalo

Ferrer’s own compositions:

Nonie Waltz

Anita Schottische

Alexandrina Mazurka

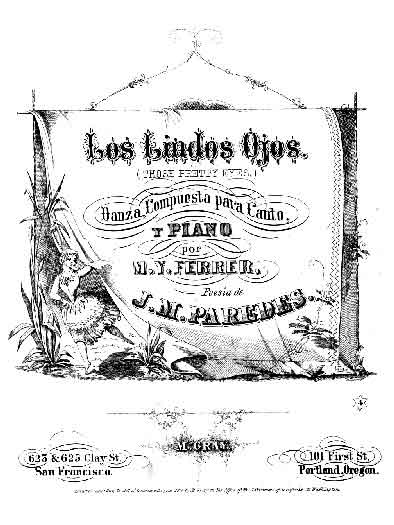

Los lindos ojos (Words by J. M. Paredes)

|

This book is also somewhat available in a modern facsimile edition from Syukhtun Editions.

Los lindos ojos, by Manuel Y. Ferrer.

Published in 1875 by Mattius Gray.

|

Some additional historic pieces arranged by Manuel Ferrer are available

in another modern publication well worth perusing: Hispanic-American Guitar by

Douglas Back (Mel Bay Publications, 2003).

El olé

A la orilla del Ebro Jota (Catanbide)

Manzanillo (A. G. Robyn)

El vito sevillano (Hernan)

Arbor Villa Mazurka (Ferrer)

Spanish Mazurka (No. 1 & No. 2)

This publication also features some other guitarists from

19th-century California: Manuel Arévalo and Luis Toribio Romero.

Romero studied guitar with both Arévalo and Ferrer.

Douglas Back describes that one of the included pieces from Romero’s

repertoire, Peruvian Air, might have come from his teacher, Manuel Ferrer.

This tune is also the tune used for La pena negra, a song from Adalaida

Kamp included in Charles Lummis’ recordings. Adalaida’s source for

the piece is José de la Rosa, who wrote the words into his word book around

1850. He may also be the author of that poem.

Overall, half of the pieces in Douglas Back’s

Hispanic-American Guitar are from California sources, a quite respectable percentage.

William J. McCoy

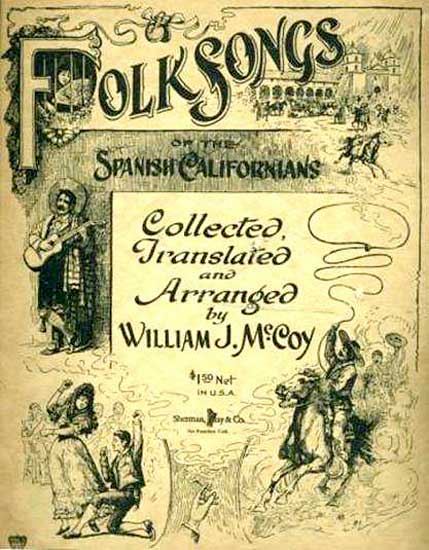

Folksongs of the Spanish Californians, by William J. McCoy

Los californios® Collection.

William J. McCoy’s song folio was first printed in 1895, and was reissued in 1926.

|

One early popular folio featuring secular music specifically

from Mexican California was that done by William J. McCoy in 1895 and published under various titles over

time, including Canciones del país de California and Folksongs of the Spanish Californians.

The pieces included are:

Me mue …

Tus ojos

Crepúsculo de amor

Ángel divino

Mitad de mi vida

El trovador

Te adoro yo

La indita

La culpa

El tormento de amor

|

With the release of Volume 9 of the Music of Early California (2007 Supplement), all of these pieces

are

again available, and in arrangements friendly to folk guitarists.

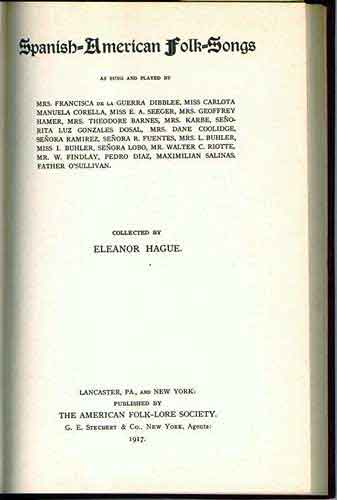

Spanish-American Folk-Songs, by Eleanor Hague

Los californios® Collection.

|

Eleanor Hague

Another popular collector and promoter of this heritage was Eleanor Hague. Her work was often published in

magazines and academic articles, and she collected many pieces together in larger publications. She was a contributor to the

publication Masterkey, published by the Southwest Museum (now part of The Autry Center).

In Spanish-American Folk-Songs, published in 1917

by the American Folk-Lore Society, she included melody lines for a good number of pieces from California, such as:

A la luz de la luna

¡Ay! vienen los yanquis

Las blancas flores

No me mates (Version of El capotín)

Carmela (Carmen, Carmela)

Los celos de Carolina

Dime, mujer adorada

Entré [a] un jardín

Levántese, niña

María, María

Media noche

Nadie me quiere

O blanca virgen, a tu ventana

¿Quieres que te ponga? (Version of Sombrero blanco)

Serenata (Era medio de la noche)

Si formas tuvieran mis pensamientos (Los pensamientos)

Todo tiene su hasta aquí (El termino)

El tormento (El tormento de amor)

El trovador

Vivo penando

Yo no sé si me quieres

Yo pienso en ti

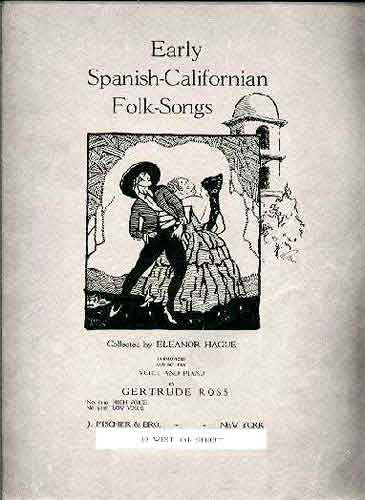

Early Spanish-Californian Folk-Songs, by Eleanor Hague

Los californios® Collection.

|

Eleanor Hague’s music folio, Early Spanish-Californian

Folk-Songs, published in 1922 with piano arrangements, was influential in preserving this music for performing musicians.

The pieces included are:

Carmela (Carmen, Carmela)

Nadie me quiere

El trovador

Un pajarito

Serenata (Era medio de la noche)

Yo no sé si me quieres

|

The collection from the Braun Research Library at the Southwest

Museum, now at The Autry Center, includes some additional pieces collected and transcribed

by Eleanor Hague, previously unpublished. Some of these reflect her own transcriptions of pieces from the

Edison wax cylinder recordings made by Charles Lummis.

Arrangements of these pieces with lead lines and guitar chords,

and usually harmony lines, are available to musicians in the

Music of Early California.

Folklore de California, by Aurelio M. Espinosa

Los californios® Collection.

|

Aurelio M. Espinosa

Aurelio M. Espinosa, who was also a noted linguist in the Spanish-language field, applied his highly developed

academic

methodology and resources to the collection of folk lore in New Mexico and California, including documention of the words

to many songs from both areas. Las Romances Tradicionales en California was printed in 1925 as part of a collection

of essays,

Homenaje a Menéndez Pidal, Tomo 1. It is the only source I have encountered to document any appreciable tradition

of

romances in California. Published in an edition of only 1000 copies, this publication is not currently readily available.

One original copy is housed at the Geisel Library at the University of California at San Diego in Special Collections.

Another point of interest in this publication, mentioned in passing, was Espinosa’s observation of

similarities between

Spanish as spoken in New Mexico and as spoken in historic California. And since Espinosa is the primary authority on the specifics

of how Spanish in New Mexico is different from Spanish spoken elsewhere, we can be assured that this is not just idle speculation.

Folklore de California, a pamphlet published in 1930, includes words to a number of songs. This

work is more

available than the previous document, but has not yet been re-printed for modern use. Included are words to:

El vaquero (El charro in Lummis’ collection)

La muerte del marido (See Esequia de Villa’s La viuda

and Adalaida Kamp’s El celoso)

Oración sobre la pasión

Jesucita Ruiz

Mañanitas de placer (See versions by Adalaida Kamp

and Manuela García)

La batalla de los tulares (A romance specifically about an

event in California)

El capitán enamorado (See Manuela García’s Capitán de un barco)

Añoranzas

El borreguito (A version of El borrego)

Por la señal

A collection of coplas populares

Unfortunately, because his interest was in the poetry, Espinosa’s

work does not include tunes.

Historic Disk Recordings

Bowmar Records Album Cover

Los californios® Collection.

This album of 78 rpm records from Bowmar Records came out in 1953. It

includes versions of a number of songs included

in Charles Lummis’ folio, some in English-language translations.

|

This 1953 collection from Bowmar Records includes:

La indita (English-language

version from McCoy)

Cántico del alba (In Spanish)

Alabado (In Spanish)

El zapatero (English-language

version from Lummis)

La noche está serena (Spanish-language

version from Lummis)

El capotín (Spanish-language

version from Lummis)

|

Decca Records Album Cover

Los californios® Collection.

|

This 1950s album of 78 RPM records from Decca also includes the

English-language versions of a number of songs included in Charles Lummis’ folio.

Charles Lummis’ Edison Wax Cylinder Recordings

Some of the most influential preservation efforts were those of one of the most

active promulgators of this romantic myth — Charles Fletcher Lummis, a transplanted Californian who

became a champion of the Southwest and its Native American and Hispanic cultures. Seeing value in

the unique heritages found in the Southwest, he attempted to get a more general American recognition

of that value. He wrote extensively about the Southwest and Mexico and, to make it accessible to this audience,

described it glowingly and romantically in terms that were calculated to try to avoid the racist

stereotypes that had prevented Americans at that time in history from appreciating these cultures.

Rosendo Uruchurtu |

Adalaida Higuera Kamp |

José de la Rosa |

Rosa and Luisa Villa and family

Manuela García |

Los del Valle |

Francisco Amate |

Lummis Folio

Rosendo Uruchurtu recording for Lummis

|

In 1903 Charles Lummis took his advocacy a step further, taking on an immense project. With his charter in

hand for

the Southwest Society, a chapter of the Archaeological Institute of America, he purchased an Edison wax cylinder recording

machine and

proceeded to “catch our archaeology alive” by recording the disappearing songs of the californios and

Native

Americans. Lummis recorded hundreds of songs from californio and indio descendants, as well as from descendants

of

Mexican immigration from the early American period. Those of the Edison wax cylinders still extant reside at the Southwest

Museum’s Braun Research Library in Highland Park, now part of The Autry Center.

The link with historic californio families was still strong when

Charles Lummis began recording songs in 1903.

As examples:

Doña Adalaida Higuera Cordero Kamp

Songs from San Buenaventura:

Traditions from Adalaida Cordero Higuera Kamp and José de la Rosa

Item Number: BK-208 CAL $15.00

|

Adalaida Higuera Cordero Kamp

|

Doña Adalaida Kamp — an informant who recorded about 65 pieces for Lummis — was

descended from the Higuera family that came to California in the 1780s. Adalaida’s mother was known for writing poetry

and, like Adalaida, for improvising verses to songs — a valued skill not only in California, but also in Spain and many

of

the former Spanish colonies. Adalaida’s recordings represent some of the oldest extant songs from California. They

are also the most difficult to transcribe. Adalaida was in her mid-sixties in 1904 when she made these recordings —

not very

old these days, but at that time she was well beyond her singing prime. Her singing is enthusiastic and sometimes even robust,

her

memory of the tunes phenomenal, but her pitch is not always true and her rhythm varies, so transcribing the pieces involves

a fair

degree of analysis. Luckily, the results are worth the trouble — these are also some of the prettiest and

most unique of the pieces Lummis documented, with a strong portrayal of the californio sense of humor and independent

spirit.

Transcriptions of the Lummis recordings of Adalaida Higuera Cordero Kamp are available as a music book:

Songs from San Buenaventura:

Traditions from Adalaida Cordero Higuera Kamp

and José de la Rosa

José de la Rosa

|

|

|

|

José de la Rosa — at two different periods of his life

|

Doña Adalaida grew up learning songs in the household where José de la Rosa, known affectionately

as Don

Pepe, resided. We see him here both as a young man and in his later years. Don Pepe, sometimes credited with being California’s

first

professional printer, came to California in 1833 with the Híjar-Padrés Party. Among his accomplishments he was

alcalde at Sonoma

for a time, and was involved in trying to obtain Mariano Vallejo’s release during the Bear Flag rebellion of 1846. He

was also a

popular musician, singer and composer who protected his material jealously so his competitors would not learn it. But he was

impressed with

the musical talent of the young Adalaida, and at his death he willed her his wordbook of songs carefully written out in his

own hand.

Adalaida recorded a great many songs from Don Pepe’s book for Lummis. Doña Adalaida in turn transcribed the words

to her own

songs, leaving both her typewritten wordbooks and Don Pepe’s word book in the archives of the Southwest Museum.

Rosa and Luisa Villa and family

Rosa and Luisa Villa

|

The californio family of Rosa and Luisa Villa came to Alta California from Baja California in 1846.

These

informants also played dance tunes on the mandolin and guitar, and were influential in later romantic revivals

of californio dances. Lummis recorded only about 20 pieces from this

family, but a number of them include harmony arrangements with instrumental accompaniment, giving more clues about how to

properly

interpret the music. Lummis also recorded some charming pieces from their mother, Esequia Asevedo de Villa.

Rosa Villa lived until 1955 to the age of 79. Luisa was still performing these pieces as late as 1939 as

part of the A la

California Orchestra at the annual A la California Club Fiestas, presented

at the Casa de Adobe by the Southwest Museum. (Check this link for more info about those programs.)

The Villa family

|

Songs from the California Traditions

of the Villa Family

Item Number: BK-202 CAL $10.00

|

Transcriptions of the the Lummis recordings of the Villa family songs

are available as a music book:

Songs from the

California Traditions of

the Villa Family

Manuela García

Manuela García

|

Music of the García Family of Los Angeles

Item Number: BK-204 CAL $10.00

|

Another of Lummis’ informants was Manuela García, born in Los Angeles

in 1869, recording 107 pieces — the largest number from any informant. An

accomplished singer with a tremendous repertoire, she grew up in a

household that sometimes included the influential Mexican guitarist Miguel

Arévalo. Most of the songs featured in the Lummis folio [see below] come

from Manuela. Many of these pieces are probably more recent in California,

coming with the Mexican immigration of the second half of the nineteenth

century, but they have become so associated with californio heritage in

the traditions of californio descendants that they have effectively merged

into that heritage.

Transcriptions of the Lummis recordings of the García Family are available as a music book:

Music of the García Family of Los Angeles:

Song Traditions of Manuela García & her Family

The del Valle Family

Charles Lummis poses at Rancho Camulos

with women from the del Valle family

|

Songs from Rancho Camulos

Item Number: BK-201 CAL $10.00

|

Lummis recorded 23 pieces at Rancho Camulos, as well as

learning dances from the del Valle family’s traditions.

Transcriptions of the Lummis recordings of the del Valle Family are available as a music book:

Songs from Rancho Camulos

A recording of those pieces, as performed by

Los californios®, is also available as a CD:

¡Qué viva la ronda!

For more information about Rancho Camulos and the del Valle family, please

click here to read the notes from the CD.

¡Qué viva la ronda!

Item Number: CD-020 CAM $15.00

|

Charles Lummis learns dances at the del Valle family home, Rancho Camulos

Despite Lummis’ familiarity with californio dance music and the fact

that some of his informants also played dance tunes, Lummis recorded only pieces that included words.

|

Francisco Amate

Francisco Amate

|

Songs from Francisco Amate

Item Number: BK-203 CAL $10.00

|

This drawing is by Hernando Villa, brother to Rosa and Luisa. Although Hernando was himself a musician and

singer,

there are no Lummis recordings of him.

Transcriptions of the Lummis recordings of Francisco Amate are available as a music book:

Songs from Francisco Amate, a Spanish vagamundo

in California

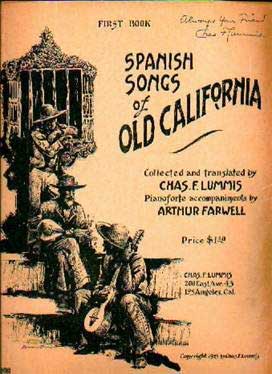

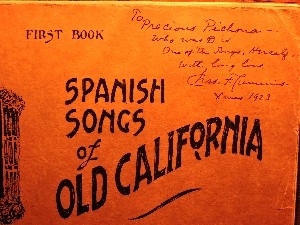

The Lummis Folio

Autographed song folio cover.

Los californios® Collection.

Charles Lummis’ song folio was published in 1923.

Los californios® Collection

|

In 1923 Lummis was able to publish 14 pieces from these recordings in an influential folio, arranged by

Arthur Farwell for ease of singing by amateurs and with singable translations.

The majority of californio songs recorded by different groups

in the 20th Century and remembered in descendent families come from that folio.

Charles Lummis Autographed book.

Los californios® Collection.

|

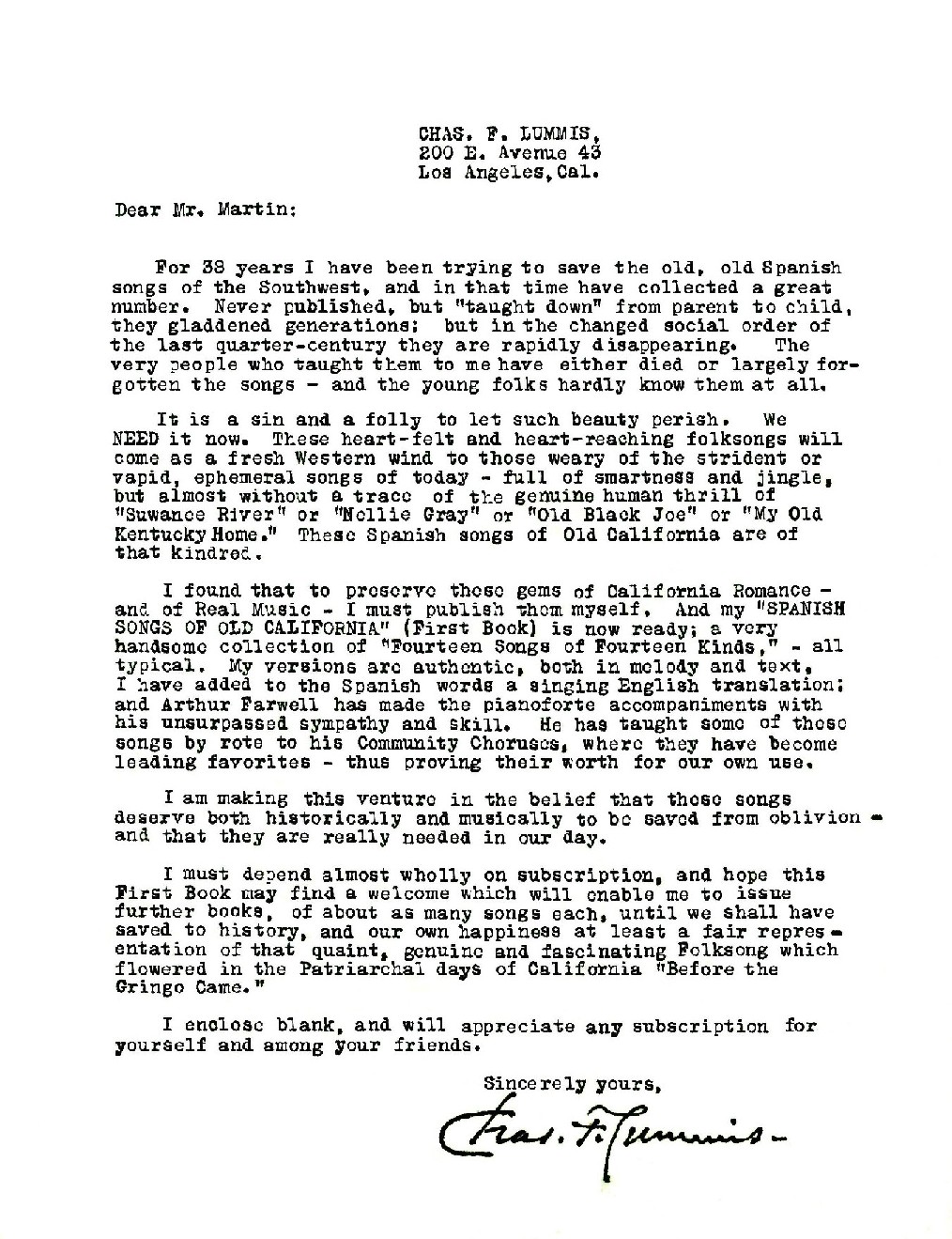

Charles Lummis Letter promoting his book.

Los californios® Collection.

|

Lummis had hoped to publish the entire body of pieces included in his recordings — on the cover of

the early

edition of his folio pictured above you will note that he thought this would be merely the first of a series of books. But

that project

was not completed in his lifetime — and there are several of us still at work completing it.

Here pictured is a copy of a promotional letter from Charles Lummis announcing the publication of this folio,

and asking for

subscriptions. in it he refers to the plan to print further transcriptions. Arthur Farwell did, in fact, transcribe many more

of the pieces in

anticipation of further projects.

Photo by Vykki Mende Gray

|

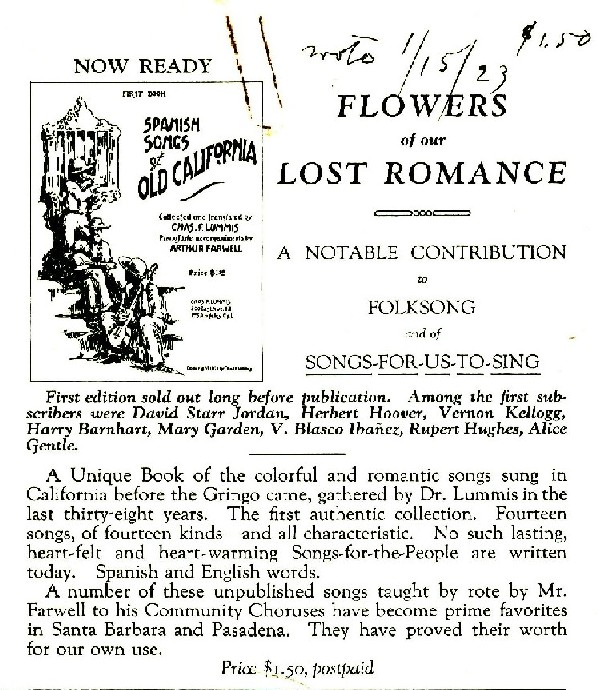

Promotional flyer.

Los californios® Collection.

|

For more complete biographical information about Lummis’

informants, consult the extensive research done by Dr. John Koegel, a recognized expert in

the field of 19th-Century Mexican music in California.

Antonio Coronel interprets californio heritage in the late 19th century.

Los californios® Collection

|

And lest one think that preserving California’s nineteenth-century Hispanic heritage consists entirely

of listening to Lummis recordings, I’d like to highlight briefly some of the other surviving

threads. For instance, Lummis did not record the Mexican and californio dance music in California,

even though he learned some of the dances, and some of the informants he recorded knew the tunes. These

informants joined other descendants, like Antonio Coronel, in efforts to keep their dances alive.

Historic postcard.

Los californios® Collection.

Charles Lummis poses with Antonio Coronel at Mission San Juan Capistrano with daughter, Turbesé

|

Nancy Fages Hogan with her parents,

Isabel C. Lopez de Fages and Alphonse B. Fages

From the Fages Collection.

As a child, Nancy Fages took lessons on the salterio

at Padua Hills Theatre.

|

Casa de Adobe Fiestas

The Annual fiestas held at the Casa de Adobe,

an adjunct of the Southwest Museum in Los Angeles, now part of

the Autry Center, were organized for many years by Isabel

Lopez de Fages who served as hostess for the Casa. Herself a descendent from early

settlers of the Spanish period, she and her husband Alphonse (Bud) Fages were involved

in a variety of activities to preserve and promote californio culture.

Los Fages lived in an adobe house built in 1840 by a cousin of Ygnacio

Palomares, the Alvarado House on the Palomares grant on the Rancho San José in

what is now Pomona.

Thanks to Brian C. Hogan for contributing addtional documentation from the Fages Family

Collection for this effort, in honor of his granparents, Isabel and Alphonse (Alfonso) Fages.

Programs

1937

Note who some of the participants of this Fiesta are and what they are doing:

Casa de Adobe Fiesta Program, 1937.

From the Fages Collection.

Now in Los californios® Collection.

Click above for larger version.

|

María Sepúlveda is Program Chairman

Music at this Fiesta was provided by

Los Trovadores de José Arias

Gabriel Ruiz is the Tecolero (dance master)

The Ruiz Dancers include:

Isabel C. Lopez de Fages and Alphonse B. Fages

Clarence and Juanita Palomares

Ricardo, Raimundo and María Sepúlveda

José and Concepción de Soto

Felipe and Esther Banks

Francisco García and Mildred Ruiz

Guillermo and Elena Walker

Eugenio Plummer, another californio dance master, is presenting a Son

A stellar cast of singers presents several pieces documented in Lummis’ recordings

1938

Casa de Adobe Fiesta Program, 1938.

From the Fages Collection.

Now in Los californios® Collection.

Click above for larger version.

|

Notice the members of the A La California Orchestra — they include Lummis

recording informants Rosa (Villa) Pemén,

Luisa Villa, and Rosendo Uruchurtu. The A La California Club later called itself

Los Californios. Eleanor Hague also

participated in these events as director

of El Jarabe Club of Pasadena.

1939

Casa de Adobe Fiesta Program, 1939.

From the Fages Collection.

Now in Los californios® Collection.

Click above for larger version.

|

Notice the members of the A La California Orchestra — they include Lummis

recording informants Rosa (Villa) Pemén,

Luisa Villa, and Rosendo Uruchurtu, as well as Gabriel Ruiz. The A La California Club later called itself

Los Californios.

Eleanor Hague also participated in these events as director

of El Jarabe Club of Pasadena.

1940

Casa de Adobe Fiesta Program, 1940.

From the Fages Collection.

Now in Los californios® Collection.

Click above for larger version.

|

Photographs

From the Fages Collection.

Now in Los californios® Collection.

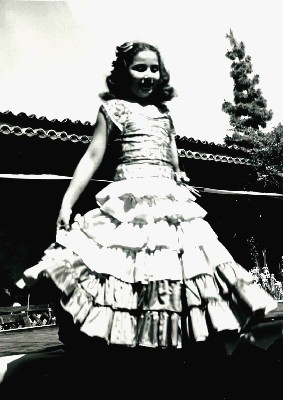

Clarence Palomares and Juanita Ávila de Palomares

dance at Padua Hills Theatre in 1963.

|

From the Fages Collection.

Now in Los californios® Collection.

Clarence and Juanita Palomares dance at a Fiesta at

Casa de Adobe about 1940.

|

The historic Rancho San José grant was made to the Palomares and Véjar

families in 1837, and La Casa Primera adobe was built that same year.

The original Palomares land grant

is also home to the Padua Hills Theatre, and the Palomares family and other members of the A la California

Club (Los Californios) were involved in sharing californio culture through that venue as well.

From the Fages Collection, courtesy of Brian C. Hogan.

Now in Los californios® Collection.

Sharon Heaton at Fiesta de la Santa Cruz, Casa Adobe

|

From the Fages Collection.

Now in Los californios® Collection.

Clarence Palomares and Juanita Ávila de Palomares at

Paul Lugo’s home for dance rehearsal in 1963.

|

From the Fages Collection, courtesy of Brian C. Hogan.

Now in Los californios® Collection.

Nancy (Fages) Hogan at Casa Adobe

|

From the Fages Collection.

Now in Los californios® Collection.

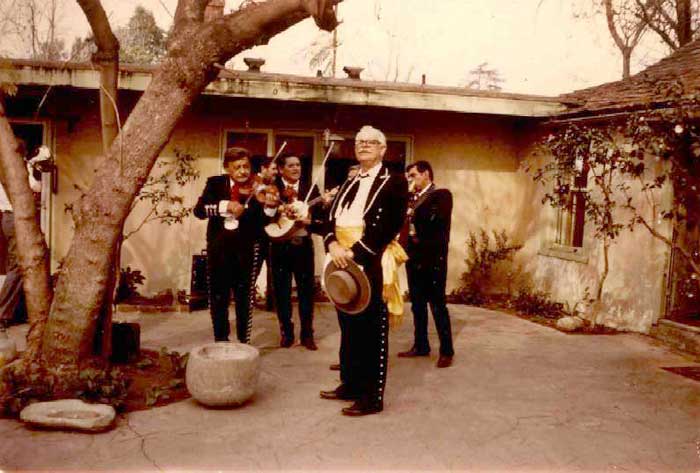

Alphonse Fages singing at La Casa Primera de Rancho San

José Adobe, March 17, 1974, Pomona, CA. Alphonse B. Fages was an artist and a favorite singer at events featuring

californio music, often singing duets with Gabriel Ruíz.

|

From the Fages Collection, courtesy of Brian C. Hogan.

Now in Los californios® Collection.

Gabriel Ruiz Dancers.

|

From the Fages Collection, courtesy of Brian C. Hogan. Now in Los californios® Collection.

Unidentified dancers at Casa Adobe

|

From the Fages Collection. Donated by Brian C. Hogan.

Now in Los californios® Collection.

Dancers at a Casa de Adobe program. Note Isabel Fages,

the woman on the far left.

|

From the Fages Collection, courtesy of Brian C. Hogan. Now in Los californios® Collection.

Isabel C. Lopez de Fages and Alphonse B. Fages.

|

From the Fages Collection, courtesy of Brian C. Hogan. Now in Los californios® Collection.

Anita and Ricarda Lugo, descendents of grantee of Rancho Santa Ana del Chino.

|

Alphonse B. Fages & Isabel C. Lopez de Fages.

From the Fages Collection.

Now in Los californios® Collection.

San Gabriel Mission in June 1976 at a Los Californios Dance

|

Other Contributers

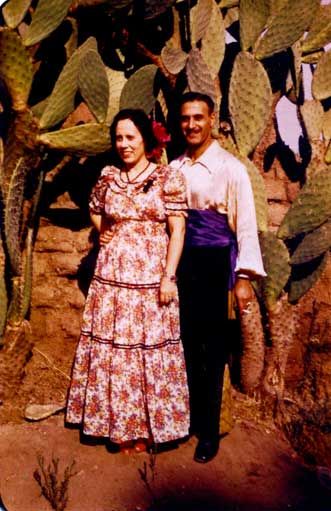

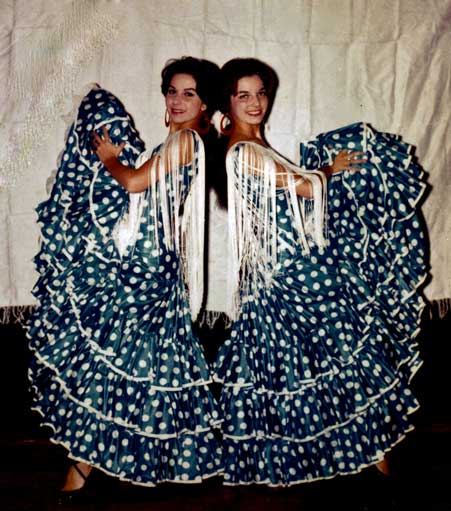

Maria Abundis and Rogelio Alfaro pictured at

Padua Hills Theater in Claremont California. In background: José

Guadalupe Rubio and Celia García

From the Fages Collection.

Now in Los californios® Collection

|

This thread in turn was picked

up by The Mexican Players and the Padua Hills Theatre — along

with the accompanying Padua Hills Orchestra. The

Claremont Community Players was founded in 1928,

and in 1932 developed the Spanish-language program

that would preserve the Mexican and californio dance,

song, and theater traditions for another two generations.

Performing Spanish-language programs for a largely

English-speaking audience, they at the same time

spoke to pride in cultural identity of those generations

of Latinos in California. Find more information about

The Mexican Players

at our Padua Hills Theatre Web Site.

The José Arias Troubadours with Mexican dancer

(José Sr. is on the right with the big smile)

Los californios® Collection

|

José Arias and his Troubadours were a family-based group of Mexican musicians in the Los Angeles area. Although

José Arias did not come to California until about 1910, he connected up with some of the same

people that Lummis had recorded. His son and grandson, also both called José Arias, still recall humorous and entertaining

visits with those informants, and the band still performs pieces learned from

those informants at the Ramona Pageant in Hemet.

The Ruiz California Dancers in 1937 at Avila Adobe in Los Angeles:

Chonita De Soto, Gabriel Ruiz, José De Soto and Eva

De Soto. Chonita and José are Palomares descendents.

From the Fages Collection, courtesy of Brian C. Hogan.

Now in Los californios® Collection.

|

Another link in the chain was californio descendent Gabriel Eulogius Ruiz. In the same A la California Club

fiestas where Luisa Villa was performing, representing a previous generation, young Gabriel Ruiz and his dance troupe,

Ruiz California Dancers (formed in 1925), were performing californio dances and music, learning them from

the

previous generation and ensuring their survival. In his later years Gabriel Ruiz undertook a project with California Alegre

to document and preserve the nineteenth-century Spanish-language music of California, especially pieces from his family, recording

an LP record called Danzas de Alta California.

Photo by Peter DuBois

From left: Vykki Mende Gray, Albert S. Pill, David Swarens

At Pío Pico home — Whittier, California

|

Many people who today know the 19th-century californio dances and dance music can credit Al Pill,

who dedicated

much of his life to keeping californio and Mexican traditional dance alive. Late in his life, he was

acutely aware of the need to make sure that these did not die with him, reaching out to younger persons

able to carry on the traditions.

One of those dancers who learned from Al Pill was Luis Goena of Santa Barbara (1928-2014), with his

group of early California dancers, Los parientes. Sadly this link with the past has now also passed on.

Another source for preservation of this music is in the traditions of southern California’s

Native American population, particularly descendants of missionized population. The Juaneño Band

of Mission Indians, Acjachemen Nation, in particular has preserved recordings of the music of their heritage,

including performance of Spanish-language based music on European instruments. This largely untapped resource

is the next great area of study for persons preserving this historic California heritage.

I’d like to close with a caution. The surviving link with the musical

heritage of Mexican California is fragile. Today many Californians of Mexican, californio or Native

California descent remember their parents, or more often grandparents, singing or dancing to the Spanish-language

nineteenth century secular music of Mexican California. But few of them actually ever learned it. In fact,

they grew up thinking it was somehow shameful to know these songs and dances. This heritage is now

entirely a revival tradition and an academic pursuit, with a continuing but often tenuous direct link

to the original sources through just a handful of researchers.

It’s important not to weaken this link further. Just because the music and its performance is colorful

and appeals to tourists, just because the purveyors of the “Fantasy Heritage” helped preserve

it for over a hundred years, doesn’t mean it should be dismissed as not being worthy of serious

attention. If we lose this heritage, we lose part of the self-identity of a large part of our future

population, as well as a piece of who we all are as Californians.

Where to find this Music

Music books and

two recorded CDs of this music,

Flowers of Our Lost Romance and

¡Qué viva la ronda!,

are available from Los californios®.

About the Author

Vykki Mende Gray is a fourth generation

San Diegan, her family

having come here in 1894. One of her previous projects in documenting traditional California music was writing

Kenny Hall’s Music Book, published by Mel Bay Publications — a collection of California old-time

music and reminiscences from Kenny Hall, acclaimed fiddler, mandolin player, and California living treasure.

Vykki is the artistic director of Los californios®, a project of San Diego Friends

of Old-Time Music.

This musical ensemble interprets the secular songs and dance music of nineteenth-century (and occasionally

eighteenth-century) Spanish and Mexican California. Vykki researches, transcribes, and arranges pieces

from original material for this group’s repertoire. Vykki is incorporating this work into her next book,

which will be on music from Mexican California. These efforts have resulted in interest in the genre, on

both sides of the Mexico/California border.

Vykki also taught

Mariachi violin classes for many years for Sherman Heights Community Center.

To contact her, email her at

info@loscalifornios.com

Groups Actively Involved Preserving This Heritage

Los californios®

is a registered trademark belonging to San Diego Friends of Old-Time Music, Inc., a California non-profit

corporation.

Contact Los californios®

at info@loscalifornios.com

Find Los californios® on Facebook.

© Vykki Mende Gray, 2020

All rights reserved.

Web design: Ellen Wallace and Vykki Mende Gray

All rights reserved.

Portal

| Los californios®

| History of This Music

| Padua Hills Theatre

| San Diego Friends of Old-Time Music

| Sitemap

|